- tags

- Life

The problem of defining life

Definitions of life have always been elusive.

Life does not exist.

— Andrew Ellington (American Chemical Society 2012).

as one focuses experimentally on any of the ‘defining’ properties of ’life’, the sharp boundary seems to blur, splitting into finer and finer sub-divisions

— Jack Szostak (J. Biomolecular Struc. Dyn. 29.4 (2012) : 599-600.)

When looking at matter down to the chemical level, it’s hard to tell what is fundamentally different between living and non-living matter. Reductionist approaches to understanding life don’t work.

Life might actually not exist physically, meaning it has nothing to do with measurable properties of matter, but rather:

“Life” is the software of reality.

What is life?

how can the events in space and time which take place *within the spatial boundary of a living organism be accounted for by Physics and Chemistry?

… living matter, while not eluding the “laws of physics” as established up to date, is likely to involve “other laws of physics” hitherto unknown

— E. Schrödinger. What is life? Cambridge University Press, 1944.

In many simulations of life, and in biology, we always think of life as structures, emergent patterns. It might be we are unable to discover life because we look for things like cellular structures and patterns. But we are not really understanding how living systems are processing information around them and involved in constructing those patterns.

Example emergent processes

Walker takes the example of satellites launched in space and the conditions of our Universe for these things to happen. We can list several:

- We need a technological (or intelligent?) civilization

- It has to understand the laws of Physics

- Etc.

Such a civilization can launch satellites because the information exists in the physical space.

Another example is the complex heavy elements that we only know about because of technology.

Life is what? Life is different from alive

This is what Walker thinks life is about: A process with the ability to do things with the Universe. Therefore, this notion is different from being “alive” in the traditional sense.

A bottle or a computer are certainly examples of life. They depend on an evolutionary process which has led us here and enabled us to construct such objects. Alive things are actively involved in information processing and constructing the reality around them.

A transition between non-living and living physics

There is a threshold in the kind of objects one can obtain. In chemical space, this corresponds to the boundary between object spontaneous appearing and object that needed active processing by an “alive” being to exist since they couldn’t have been created through random search or random assembly of modules.

With this new approach, the quote saying that life is the software of reality becomes slightly clearer: it is the software that runs on top of reality and actively modifies it in the process, creating what we observe as “living” systems.

Towards quantifying life - Abstracting universal biochemistry

Life is a process where information structures matter across space and time.

So far, people have been mostly focusing on the “building blocks” of life. With life on earth, everything shares a common basic biochemistry. General building blocks of life are understood with this sample 1 bias of earth’s biochemistry. Life emerging from ALife systems might work very differently.

Universality:

- In biochemistry this means that all life on earth shares a sort of common basic details

- In physics it is more about some macroscopic properties of a system. If very different systems share a common macro-property, the property is considered universal.

Can we find a universality class for life?

We can think of information processing as a general property we can study. Walker focuses on the restricted problem of finding a universality class in patterns that emerge from biochemistry alone.

Life in the chemical space

The chemical space is extremely large (possible combinations of molecules). But because it is so large, there are a lot of chemical elements that require information about how to make them for them to have appeared in the first place and for the Universe to produce them in any abundance. For example, large proteins couldn’t have emerged through random processes.

Earth as a large ensemble of biochemical networks

When looking at Earth, organisms can be seen as partitions of the global biochemistry. The cell is probably not the right boundary to be looking at because cells are interacting through chemical reactions with an environment and modifying it, thereby defining a larger “network” that can be defined as living.

Measuring scaling behavior

Walker’s group sampled ensembles of biochemical networks that exist across different scales of the biosphere(species, ecosystems, biosphere) and tried to look for global patterns and universality classes.

The experiments were based on comparing properties of these networks and scaling properties against random chemistry examples.

It seems from these experiments that there are well behaved scaling laws that work across individuals, ecosystems and the biosphere. It also seems that they are significantly different from randomly sampled, similarly sized chemical networks. However, the behavior was reproduced with frequency based sampling.

There is a large fraction of reactions and compounds that is shared across all domains of life on earth.

Coarse-graining to find universal properties of chemical reactions

The idea here is that although all living things might not share the same chemistry as Earth’s, there might be patterns and regularities that are common at higher coarse-grained scales.

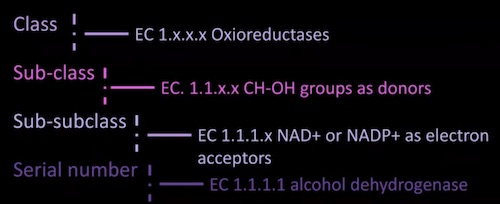

Enzyme commission numbers is a readily available classification of chemical reactions that is hierarchical.

Figure 1: Slide from Sara Walker’s talk

At the coarsest level (EC1, EC2, etc.), more or less regular scaling behavior is observed for each of them across multiple life scales.

EC1 has very consistent super-linear scaling laws that can be fitted to it and EC6 has sub-linear scaling.

Universality classes (scaling behavior) observed are not explained by the presence of these enzymes in all biochemical reactions.

It is likely that these neat scaling behaviors cannot exist at the smallest level of EC. What scale does universality appear at and what does this mean for life and emergence?

At the second level (ECx.x), the scaling behavior is still very much present.

Scaling behavior has also been observed in % of chiral molecules within networks.

Models of LUCA also fit the scaling behavior previously mentioned.